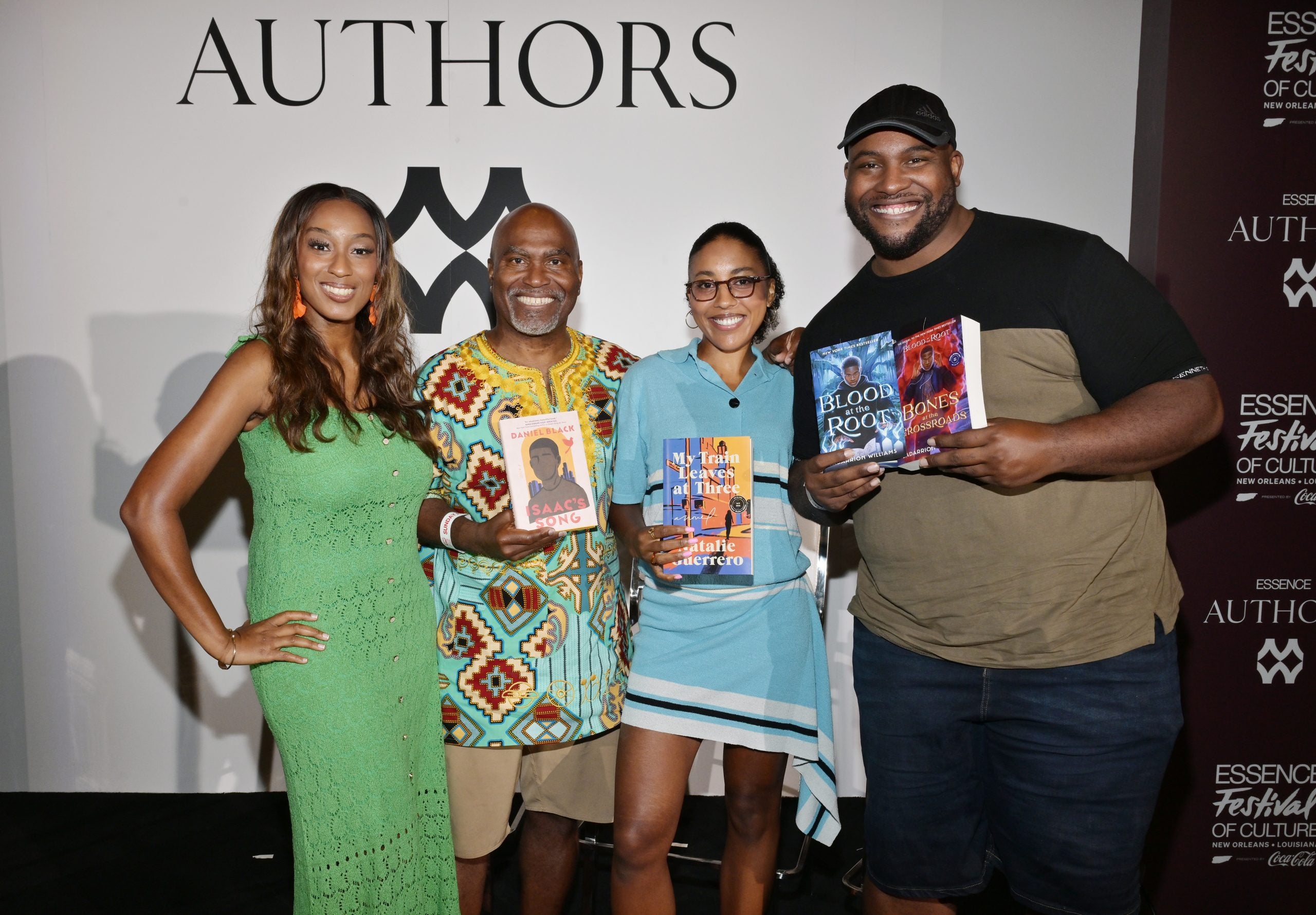

The stage became a sanctuary for truth-telling and storytelling during the “Songs in the Key of Life: Navigating Identity and Dreams in Modern Fiction” panel at the 2025 ESSENCE Festival of Culture in New Orleans.

Moderated by ESSENCE Senior News & Travel Editor Melissa Noel, the conversation focused on creating Black characters who don’t have to be likable, palatable, or perfect to be powerful.

Dr. Daniel Black, author of Isaac’s Song, opened up about crafting characters rooted in real life. “Black people are characters by definition,” he said. “We’re funny, we’re complex, we’re wise, we’re crazy, right? We’re wounded, we’re healers. We’re all the things.”

His novel follows a queer Black man seeking healing in 1980s Chicago — a journey that mirrors the author’s commitment to capturing the full, divine humanity of Black men. “When you start creating characters, it’s like, how do you make people fall in love with characters who don’t look like Christ?” he told the audience. “Flaws are divine.”

Natalie Guerrero, whose debut novel, My Train Leaves at Three, is set to drop on July 15, leaned into the theme of imperfection. Her main character, Xiomara, is grieving, broke and far from agreeable — and that’s exactly the point. “If you’re not a good Black woman, then what are you in this society?” she asked. “I really wanted her to find legs to break out of that and be able to just be and exist.” She continued, “I really didn’t want to put the pressure on my main character to be good or palatable.” Guerrero explained she only trusted scenes where her character acted honestly, even when that honesty was ugly.

For LaDarrion Williams, who authored the bestselling Blood at the Root, fantasy became the backdrop for emotional reality. The young adult novel follows Malik, a Black teen discovering magic, and himself, at a fictional HBCU. Williams recalled how Black boys like Malik were often erased or underdeveloped in the genre.

“They would be killed off to teach everybody else about racism,” he said. “But in them being killed off, you didn’t get to learn their interiority.” That’s why his non-negotiable was having a dark-skinned Black boy on the cover, commanding ancestral power beneath a Spanish moss tree.

The conversation also touched on removing the white gaze from Black storytelling. “Then we can really tell ourselves the truth,” Black said. He later added, “The joy of a Black kid going to a Black college is intelligence. It is not an achievement. Intelligence is who you are.”

As the conversation deepened, the authors shared powerful moments of impact: Guerrero recounted a reader’s heartfelt message about finally feeling seen through her novel; Williams spoke of incarcerated young men who connected deeply with his work; and Black reflected on how years of storytelling have led to potential Hollywood adaptations of his books, reminding the audience of literature’s power to shape culture.

By the end of the panel, it was clear: modern Black fiction isn’t afraid to go deep, get messy and hold space for the fullness of our experiences. Whether through magic, grief or characters unapologetically chasing their dreams, each author reminded us that storytelling is healing and that every flaw, every truth, belongs on the page.