To put it plainly, Sarah Diouf is an image architect. The designer with a degree in visual communication spent the better part of her early twenties spearheading a magazine. She tells me over a call that this portion of her life fueled her creative passion alongside storytelling. As the founder of Tongoro, a brand that possesses a charming aesthetic, Diouf’s designs have been worn by Alicia Keys, Naomi Campbell, and Beyoncé. The latter opted to wear Tongoro alongside 30 dancers onstage during her “Renaissance” tour.

Born in Paris to a Senegalese father and a Central African–Senegalese mother, Sarah Diouf’s early life was shaped by movement and multicultural influences. Both of her parents worked for the now-defunct pan-African airline Air Afrique—her father as a pilot and her mother as a stewardess, which afforded Diouf the chance to travel widely from a young age.

In the early 2000s, amid political instability and a military coup in Côte d’Ivoire, Diouf was sent back to Paris by her mother, having lived all her life in Abidjan. The French school she had been attending was facing closure, and her family sought stability. She moved in with her aunt and continued her education in France, something she describes as a new beginning for her. There she went through high school, then did a two-year diploma in Velizy, a city outside of Paris, where she studied techniques of commercialisation, including marketing and sales fundamentals. Chronologically, this took place before Diouf applied for a master’s in business school and studied marketing and visual communication at the INSEEC School of Business and Economics Paris.

In 2008, her life took a dramatic turn after she was involved in a serious car accident while riding her Vespa. The collision left her hospitalized for an extended period with multiple injuries, forcing her to take a year off from business school and pause her academic pursuits. Confined to bed and outfitted with a neck brace, Diouf faced a long and challenging recovery. But it was also during this downtime that a new chapter began for her.

“My mother had gotten me a portable computer,” she says. “It was my first MacBook, and because of the rise of the internet, [everyone] was starting [a] blog.” Because she was stuck in bed with neck support, she was unable to take pictures of herself and become a fashion blogger. However, her love for imagery and world-building persisted. Diouf felt she could create a platform to showcase what she had an affinity for.

With that burst of energy, she launched Ghubar, an online magazine that reflected her passions about diversity, African creativity, and a fascination with the Middle East. “I’ve always been drawn to Arabic culture and philosophy,” Diouf reflects. “After the accident, I felt like I could have lost my life, so I needed to do something meaningful.”

What began as a creative outlet among friends quickly evolved into a vibrant collective. Introduced through mutual connections, Sarah and a group of ten young creatives formed a small but passionate team behind Ghubar, which gained popularity within the Paris fashion scene and attracted collaborative opportunities with companies like Reebok and even the automotive brand Audi.

What Ghubar did was lay the groundwork for her future as a designer; she was able to see the industry from every angle through her experiences interviewing designers and creatives. She had realized that most of the African brands were positioning themselves as luxury, determined to change the narrative; she began to envision a brand that would be both accessible to a global audience and capable of redefining how African design and production were perceived.

By 2011, she started making regular trips back to Dakar, visiting every two to three months. It became a routine. “I didn’t attend fashion school, but I went to business school. And so what I knew for sure is that if I were to launch something, it needed to be commercially viable and it needed to make money,” she tells ESSENCE.com. She spent a year developing a business plan and setting aside capital. In 2015, she introduced her first capsule collection as a test run. A friend in Paris, who ran a concept store highlighting African fashion designers, was hosting a pop-up in the spring of that year. Diouf saw an opportunity. “I asked if I could participate because I wanted people to actually try the clothes, feel the fabric, and give honest feedback,” she explains. “She brought 50 pieces to the pop-up—and they all sold out.” By 2016, she launched Tongoro, kickstarting her career as a fashion designer and entrepreneur.

Tongoro serves as a ready-to-wear brand that dresses global customers, offering a unique taste that fosters the “made in Africa” label while seeking inspiration in African sartorial technique and further preserving them. Diouf’s silhouette is often renowned for its looseness and grace in motion, frequently playing with oversized and exaggerated forms: wide-legged trousers, voluminous dresses, and kaftan-inspired cuts that blend feminine sensuality with plain flattery.

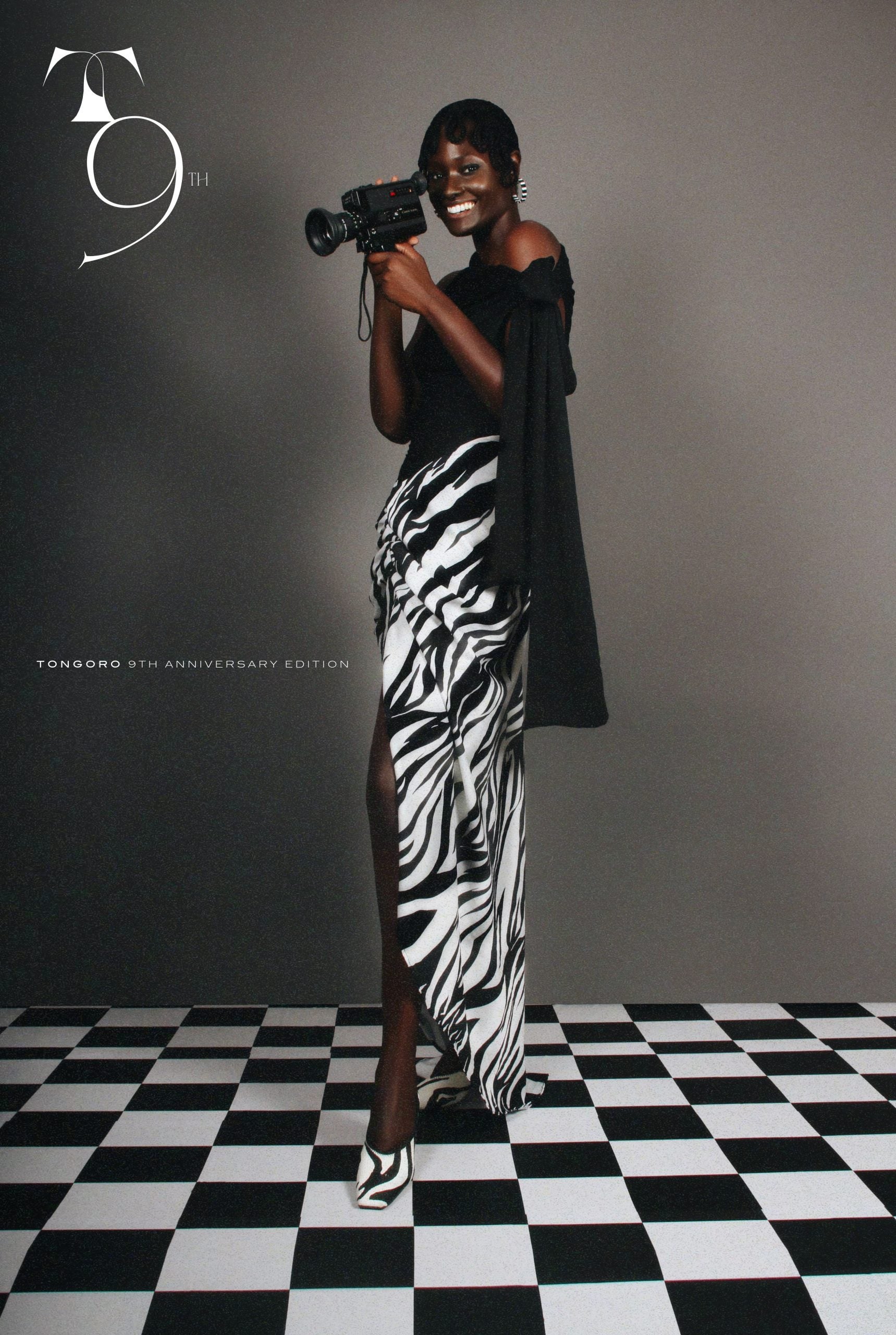

The designer’s use of color is also about delicate balances. Diouf was inspired by the 1960s legendary African photographers to create the black and white palette that has come to be associated with the brand. To her, these monochromatic portraits bolster an African aesthetic due to their classic feel that stands the test of time.

“To create solely in black and white was something I never thought was done with African fashion,” she explains. “I thought if I wanted to create a difference, I needed something that stood out. Something people would see and know that’s Tongoro, whether it’s in the shape, in the style or in the print, and I was going back to my school books and finding what makes a brand strong. That’s how I built the DNA of the brand. ”

Creating a couture line wasn’t originally in the books for Sarah but with the hundreds of requests for red carpet looks and weddings, it was what her customers wanted, so she listened. Inspired by the structure of the boubou, and featuring eccentric African details, opulent gold accents, and rich suedes, the couture line has become one of the recent successes of the brand.

Her ninth anniversary drop is broadly inspired by her favorite 1960s photographers: Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, and Okhai Ojeikere–all whose images are captured in black and white. “We are going back to the source,” the designer shared.

2025 marks Tongoro’s ninth year in business, and for Diouf, it feels like a blessing, not because she’s a deeply spiritual person who believes in nine as a number of completion, but because whenever she looks back, it feels surreal. She says she can look back on her past goals and reflect on how she’s achieved all of them.

Her goals for Tongoro’s tenth year include scaling the brand into the global market even further, producing at a scale that can compete with global brands while still staying ethical and sustainable. And she’s been having the conversation as of late, reimagining not just for Tongorno’s future but for the future of African fashion. “My major foresight is how do we create success in the way it has been created in the West, fashion is a billion-dollar industry in the West, how do we create the same in Africa, how do we go scale artisanal further?”